The look-and-say sequence is a series of integers. It can grow indefinitely. It is generated by reciting a number phonetically, and writing what you spoke numerically. Its popularity is attributed to famed cryptographer Robert Morris. It was introduced by mathematician John Conway. It looks like this:

1 11 21 1211 111221 312211 13112221

The first line would be pronounced as “one 1”, and then written as “11” on the second line. That record would be spoken as “two 1’s”, giving us the third line “21”. The greatest individual symbol you’ll ever find in this consecution is a 3.

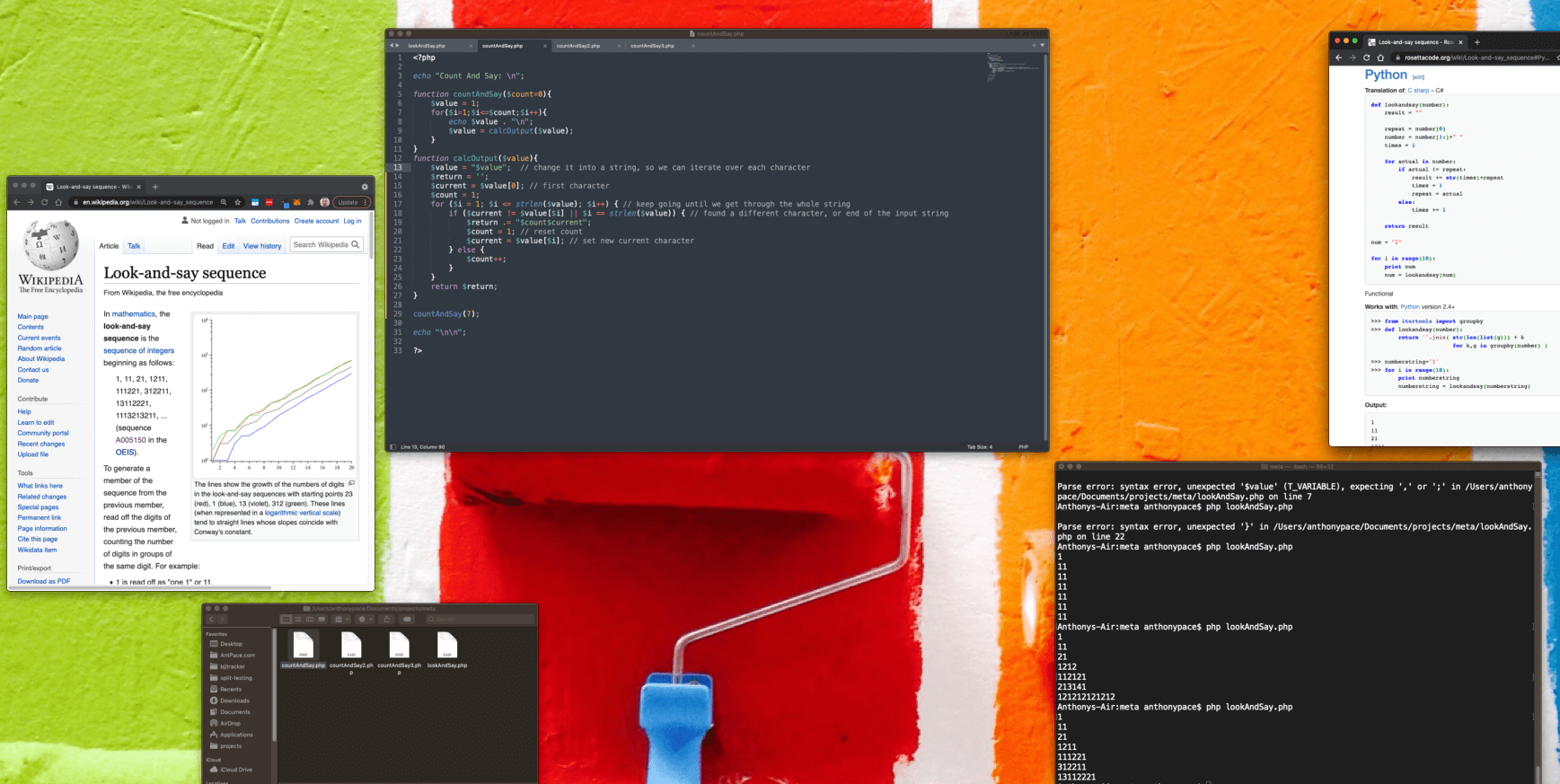

This topic has lots of trivia, variations, and history that could be dug up and expounded upon. Here, I’ll explain a solution written in PHP to produce this chain of numerals. The input will be the count of how many lines, or iterations, in the series to generate. Below is the code:

<?php

echo "Count And Say: \n";

function countAndSay($count=0){

$value = 1; // initial seed

for($i=1;$i<=$count;$i++){

echo $value . "\n";

$value = calcOutput($value);

}

}

function calcOutput($value){

$value = "$value"; // change it into a string, so we can iterate over each character

$current = $value[0]; // first character

$count = 1;

$return = '';

for ($i = 1; $i <= strlen($value); $i++) { // keep going until we get through the whole string

if ($current != $value[$i] || $i == strlen($value)) { // found a different character, or end of the input string

$return .= "$count$current";

$count = 1; // reset count

$current = $value[$i]; // set new current character

} else {

$count++;

}

}

return $return;

}

countAndSay(7);

echo "\n\n";

?>

I separated my code into two functions. I think this is the best approach. As an exercise, see if you can figure out how to refactor it into one. This could help you to internalize the logic as you write it out for yourself.

The initial seed value is “1”, and that is hard-coded at the top. The for-loop iterates based on the count input parameter. That means the code circles back and re-runs, with updated values, until its internal count (represented by the variable $i ) matches the $count variable passed into countAndSay($count).

The code that we loop over outputs the current sequence value (starting with 1) as its own line (“\n” will output a new line in most programming languages) , and then calculates the next. The function that determines the next line of output, calcOutput($value), takes the current value as an argument.

The first thing we do is cast the integer value passed along into a string. This lets us refer to each character by index – starting at zero – and save it to a variable $current. We start a new $count, to keep track of how many times we see the same digit.

The next for-loop executes for the length of the $value string. On each loop, we check if the $current character we saved matches the subsequent one in that $value string. It is again referenced by index, this time based on the for-loop’s iteration count represented by the variable $i.

If it does match, one is added to the $count variable that is keeping track of how many times we see the same character is a row. If it doesn’t match (or we’ve reached the end of the input), the $count and $current number are concatenated to the $return element. At that point, the $count is reset to 1, and the $current value is updated.

Writing an algorithm to generate the look-and-say (also known as, count-and-say) sequence is a common coding puzzle. You might run into it during a job interview as a software engineer. As practice, see if you can simplify my example code, or even write it in a different programming language than PHP.